A guide to one-on-ones

Much has been written on the topic of one-on-ones recently, but the advice is either the-same-old platitudes or takes the form of “4 things you can do transform your one-on-ones”, which is a quick read and a quick forget. This article aims to cover the topic of one-on-one more fully, from inspirational principle to prescriptive mechanics. It is based on my own experience and the writing of some of the greats in engineering management.

Me: “Are you aware that your manager Tim has not met with any of his employees in the past six months?”

Steve: “No.”

Me: “Now that you are aware, do you realize that there is no possible way for him to even be informed as to whether or not his organization is good or bad?”

Steve: “Yes.”

Me: “In summary, you and Tim are preventing me from achieving my one and only goal… As a result, if Tim doesn’t meet with each one of his employees in the next 24 hours, I will have no choice but to fire him and to fire you. Are we clear?”

Steve: “Crystal.”— Ben Horowitz, “Hard thing about hard things”

The one-on-one is the heartbeat of modern engineering management. But that was not always the case. I assume it would be quite challenging to pinpoint the exact origin of the one-on-one. The earliest reference I could find was from the mid-1980s where Andy Grove said that “regularly scheduled one-on-ones are highly unusual outside of Intel.” Somewhere along the last thirty years, this management ritual went from being highly unusual to perhaps the most recognizable activity a manager does today.

I once asked a coworker what he thought managers spent their time doing, and he said: One-on-ones and stuff. It’s a surprisingly common mental model of a manager’s time. We do some stuff, and of course, one-on-ones.

However, its status as the manager’s de facto activity is also what makes the one-on-one daunting for inexperienced leaders to pick up.

On my first day as a manager, I sat down to schedule meetings with every member of the team. I knew it was somehow important — or at the very least, expected — but even scheduling one felt awkward. For the more junior members of the team, it wasn’t so bad. I was already mentoring them and a one-on-one felt like a natural evolutionary step forward. But as I went down the list and arrived at the two staff engineers, I hesitated. Just yesterday they were my peers, developers I had worked alongside over the past two years. A one-on-one with them would feel like such a strong expression of I AM YOUR BOSS NOW! that it could only possibly be received with judgment and resentment right? So troubling to me were these fears, that I asked the director of the team to continue holding his one-on-ones with them, and that I would just start with the junior developers. The result was a confusing and awkward transition that dragged on for months.

What role does the one-on-one play that makes it so integral to a healthy team?

Leadership books love using metaphors to explain management concepts. The most common metaphor for the one-on-one is the bridge (you can already guess what the lessons there are). But, as we all know, arguments by metaphor are lazy and often result in faulty reasoning and inadequate conclusions...

So here’s MY favorite metaphor for a one-on-one.

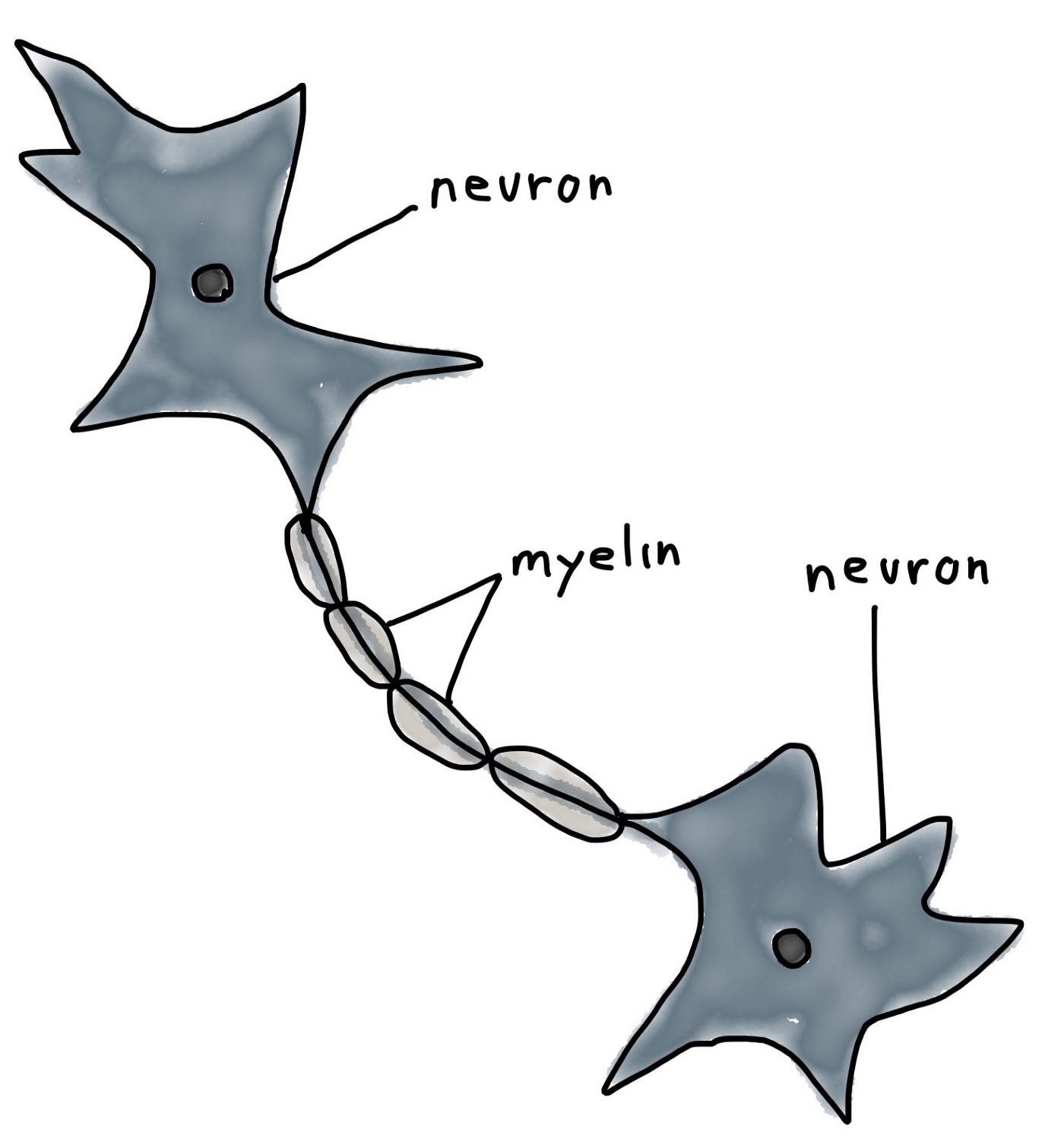

Have you heard of myelin?

Strengthening the connection

We are all familiar with the fact that neurons are the basic cellular building block of the brain. A single neuron is not capable of much, but a network of neurons is what enables life’s complexity like emotions, memory, and learning. Neurons are connected to each other by nerve fibers that carry electrical signals. Here’s the beautiful thing, as two neurons interact more and more they trigger the production of a substance called myelin. Similarly to cable insulation, myelin is a fatty sheath that wraps around the nerve fiber and serves to increase the speed and strength of electrical communication between neurons.

How important is myelin? It plays a considerable role in skill development. For example, the amount of practice that an expert piano player gets correlates with the amount of myelin density in regions of the brain related to finger motor skills, visual, and auditory processing centers.

This is why myelin is an excellent metaphor for the importance of one-on-ones.

- It increases the strength and speed of information between two parties.

- It cannot be consciously created; instead, repeated use of that channel is required for organic growth.

- Performance can be increased by the deliberate use of the information channel through practice.

To put it more directly, the one-on-one is not about having deep heart-to-heart conversations or talking someone out of leaving. No, the primary goal of the one-on-one is to build and maintain an efficient information channel between you and the people on your team. It lowers the barrier to entry for communication and therefore encourages higher volume and quality of information exchange.

If that doesn’t sound sexy, is because it’s not. Practice rarely is. But the investment of continuously exercising that communication channel through one-on-ones will pay management dividends for years to come.

Given this principle, here are the three non-negotiable one-on-one rules for new managers.

The Rules

- Frequency: Once a week. This is the industry-standard cadence for one-on-ones, and it’s a good one. It’s frequent enough to nullify recency bias and problem festering. It also buffers the occasional skip if someone is not available.

- Length: 30 to 45 minutes. Anything less than that and you will likely not even get through the handshake conversations that happen at the beginning of every one-on-one. At least thirty minutes gives you the option to discuss difficult topics.

- Listening: Listen for more than 66 percent of the time.

“But wait a second Chris, I had a great boss that didn’t follow all of these rules.”

“Yes, these are non-negotiable rules for a new manager. When you can run an org with your eyes closed, feel free to branch out!”

“But this list seems to be missing other rules that I heard about?”

“We’ll get to the mechanics later. These are just the non-negotiables.”

But first, the point on listening deserves emphasis.

On Listening

“The manager should do 10 percent of the talking and 90 percent of the listening. Note that this is the opposite of most one-on-ones.”

— Ben Horowitz, “Hard things about hard things”

We are tired of hearing that we should be talking less and listening more, but, like someone once said: people need to be reminded more often than they need to be instructed. And at the risk of sounding like Oprah, I am obligated to say that listening is more than just not talking.

A helpful mentality for a manager to take on during their one-on-one is of an interviewer asking questions to a nervous guest. And like the best interviewers, your goal is to get your guest to feel comfortable and to talk extensively about what matters to them.

“What is the role of the supervisor in a one-on-one? He should facilitate the subordinate’s expression of what’s going on and what’s bothering him. The supervisor is there to learn and to coach… How is this done? By applying Grove’s Principle of Didactic Management, “Ask one more question!” When the supervisor thinks the subordinate has said all he wants to about a subject, he should ask another question. He should try to keep the flow of thoughts coming by prompting the subordinate with queries until both feel satisfied that they have gotten to the bottom of a problem.”

— Andy Grove, “High Output Management”

Follow Grove’s Principle of Didactic Management: Ask one more question!

First, recognize that the person on your team is optimizing for not sounding stupid in front of their boss. By speaking before asking, you will quickly silence any opposing views and prevent them from ever being shared.

Second, if what you’re hearing is grating, listen twice as hard. Resist the temptation to start formulating an answer while they are talking. Nothing kills trust like having your report work up the courage to tell you how bad their situation is, only to have you deny there’s a problem, defend the status quo, then consider the problem solved and ignore it.

Third, recognize that what concerns you is not necessarily what they have in mind. Ask questions to precisely understand where they are coming from. This allows you to shed some of your assumptions and tailor an answer to address their actual questions.

Here’s an experience I had that illustrates the last point. “Georgia, how are you feeling about the team?”

“I’m worried about the recent turnover, it’s never great to have good people leave?

I tensed up. She was clearly wondering why her coworkers were leaving and whether she should too. My instinct was to put on my manager hat and try to salvage the situation before it got worse. But, I remembered to ask one more question.

“What about it makes you worried?”

“Well, now that Carlos is gone, there’s a huge gap in our front-end knowledge. I’m worried about our velocity and ability to hit the March deadline.”

I breathe a sigh of relief. “You’re right. What do you think we should do?”

Had I jumped the gun, I would have been way off-target, going on and on about an imaginary morale issue. Even worse, she would have probably just nodded along as her actual concern continued to go unaddressed.

Always ask one more question.

The Mechanics

Now that you understand the principle and heard the lecture on listening, shall we get to the mechanics of one-on-ones?

This is a list of best practices that can help focus and improve the effectiveness of your one-on-ones. The list may seem overwhelming at first, but the idea is not to adopt everything. Pick a few things that fit your management style and try them out.

It’s fine if you don’t end up doing most of these. I’ve known great managers who ran casual and unstructured one-on-ones, and some bad managers that had a proper document and agenda.

General

- Respect the schedule: Don’t consistently cancel or be tardy to your one-on-ones. If something comes up, reach out and reschedule. It signals that you care. Almost every meeting will be more urgent than your one-on-ones but try to uphold their importance.

- “What’s on your mind”: This has become the standard opener for one-on-ones. It’s soft but effective. It often serves as a signal for both parties to exit small-talk-ville and enter serious-talk-central.

- Don’t end with “anything else?”: This is not a big deal, but try switching the phrase “anything else?” with “what else do you want to talk about?”. They both accomplish the same thing but the latter doesn’t make it sound like you are trying to wrap things up.

- Have an ongoing document: If you find that your one-on-ones are lacking quality or follow through, start a private document between you and your report and attach it to the calendar invite. Create an entry per meeting and have both parties fill out an agenda ahead of time. During the session, write down actionable items to follow-up on. Only use this if both of you are committed to following through. It’s very frustrating for one party to diligently adhere to the process and have it be ignored by the other. Note that this can make the one-on-one feel overly professional.

Progress Report

Generally considered an anti-pattern for one-on-ones, but the progress report has its place. Its presence is common at the beginning of the meeting and often serves as a jumping point to other substantive topics. The more hands-on you are as a manager — which you should be if you’re a line manager — the less useful the progress report is, so make sure that your conversations move beyond it.

If someone on your team only brings a progress report to their one-on-ones, then they either don’t know what to talk about (you should fix this), or they don’t trust you and want the conversation to stay on surface topics (you should definitely fix this).

Note that, as a manager, your own one-on-ones will appropriately include a large portion of progress reporting. Your manager is not intimately involved in the team’s day-to-day work. Therefore, in that meeting, you represent not only yourself but also the team.

Interpersonal

If one-on-ones with a specific member on the team is feeling impersonal, you should spend dedicated time getting to know each other. Kim Scott suggests sharing life stories from elementary school up to now. It’s usually an awkward start, but people get pretty comfortable telling their story. Make sure to ask a lot of questions along the way about their hobbies, previous organizations, and worst bosses. Note that your reports will expect you to remember the significant parts so pay attention.

If all of your one-on-ones feel impersonal, then you’re likely the problem. One-on-ones are a great canary test for how much your team trusts you. The likely culprits are:

- You don’t have a track record of listening.

- You don’t have a track record of following up.

- You don’t share enough of yourself, and the relationship feels one way.

- Your team doesn’t respect your vision and/or your technical ability to deliver it.

Coaching

This should be an integral part of your one-on-ones, especially with newer or more junior members of your team. You may be intimidated by the exercise, but your team is not. They are invested in their own growth and understand that feedback is a critical driver of it.

- Write down feedback throughout the week as you see specific behavior, then bring it up during the one-on-one. I notice that you get a lot of feedback on your PRs about missing tests. Do you feel like that feedback is valid? What are your general thoughts on testing?

- If your company does annual performance reviews, you can coach your team by revisiting development plans during your one-on-ones. One of the things we talked about during our performance review was your desire to do more public speaking. How’s that going?

- If your company has a leveling doc, go over the different attributes of developers at their current level and the next level. How do you think you’re doing on the organizational impact aspect?

“What about senior members that are beyond my own technical abilities? Do I still coach them?” Yes. Managing senior talent can be challenging and deserves its own article, but the least you can do here is keep them accountable to their own growth plans (and help them create one if they don’t have one). Steph Curry still has a shooting coach.

“I would love to coach my team but I honestly don’t know enough about their individual work to properly do it.” You’re likely too hands-off and need to get more involved with the team’s day-to-day immediately.

Get their perspective

As a manager, you often have a better view of the forest, but your team sees the bark and grooves on the trees. Ask questions that will help you understand what is happening down in the trenches. And share your vantage point to help them see where they fit.

Example questions:

- What did you think about the last all-hands presentation?

- Who is totally delivering and kicking butt?

- What’s the worst part about working here? What could we be doing better?

- What do you hate most about our product?

- What do you think about the new executive we hired?

- What’s one piece of infrastructure that we’re missing?

- On a scale from 1–10, how would you rate your job satisfaction right now? How can I help move that up by one point?

Approach this breadth-first. The last thing you want to do is interrogate someone on a topic they have no interest in. Ask one or two questions on each topic then move on until you find a nugget of something to discuss and explore.

If all else fails, talk about what’s bothering you and get their opinions on it. It helps your team identify what are the current issues on your mind and gets you some creative solutions. We’re struggling to get participation in team meetings. Have you ever seen a team that did that really well? What did they do?

Crisis

Your manager senses will immediately tell you when your one-on-one is headed towards a crisis. The sources may vary, but the feelings are always negative and intense. Maybe they are mad at you, or frustrated with the company, or disappointed in themselves. Can you believe that Bob’s team took down production again!? Sometimes it has nothing to do with work, and they just got a lot going on their personal lives.

Be empathetic and listen. Keep your emotional reaction in check to prevent a positive feedback loop that spirals the situation out of control.

In these situations, silence is often more appropriate than asking questions. The person has something to say, and they just need to say it. Your clarifying questions or attempts to reframe are just interruptions that will frustrate more than help. Your greatest contribution is silence.

Once the release valve is losing steam and the pressure seems to have balanced out, then you can start to solution.

Career Development

The general view is that a good one-on-one culture is less about project updates and more about important things like career development. In my experience, this topic is a little bit of a mixed bag. Some engineers love to have them, and others would rather talk about literally anything else. Tailor the frequency to their interest but aim for around once a quarter.

Questions you can ask: What areas do you want to grow towards? What does your next job look like? How can you build towards that while working here?

I would love to hear more suggestions for other one-on-one mechanics that have worked for people.

The Conclusion

I tried but failed to write a better conclusion than rands did on the importance of one-on-ones. So I’ll leave you with his.

The sound that surrounds a successful regiment of one-on-ones is silence. All of the listening, questioning, and discussion that happens during a one-on-one is managerial preventative maintenance. You’ll see when interest in a project begins to wane and take action before it becomes job dissatisfaction. You’ll hear about tension between two employees and moderate a discussion before it becomes a yelling match in a meeting. Your reward for a culture of healthy one-on-ones is a distinct lack of drama.

— Michael Lopp, “Managing Humans”