Debugging Your Engineering Career (ELC: Wade Chambers)

Since you graduated college, you’ve been on a steep growth trajectory, getting promoted every couple of years. However, in the last few years, things have taken a turn for the worse. You don’t feel like you’re learning as much, and no one will spell out what you need to do to get your next promotion. You tried to switch your team, manager, and company, but it didn’t help. Your team and peers seem to like and respect you. Even though you’re not the best person in this role, you would put yourself in the top 5%. What’s wrong with your career?

I’ve been versions of the paragraph above a few times in my career. I found myself in a place where I wasn’t necessarily failing, but I wasn’t growing either, and I didn’t know how to get unstuck. In this post, we’ll be going over Wade Chamber’s talk on Debugging Your Career that he gave at ELC Summit 2020.

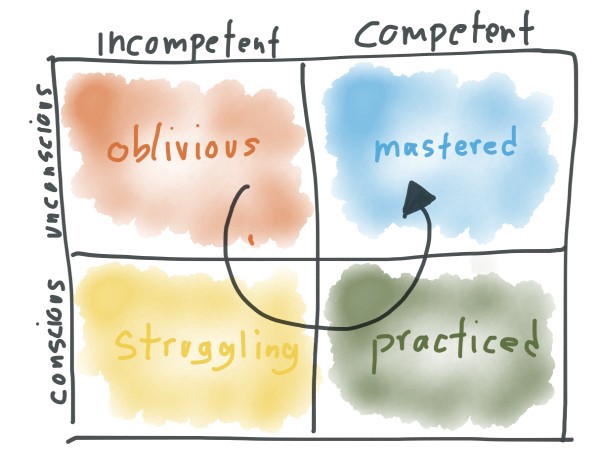

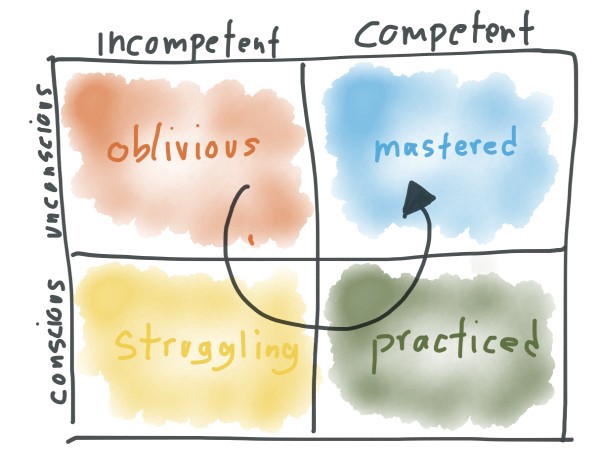

Wade guides us through how to go from the oblivious state of unconscious incompetence to the mastery state of unconscious competence.

Oblivious: The Peter principle and why people fail

Peter Principle: People in a hierarchy tend to rise to their “level of incompetence

We start our journey in unconscious incompetence. In this phase, not only do we not have the skills required to be successful at our role, but we’re often not even aware of it. Our significant blind spots lead us to have an overly inflated assessment of our own work.

A study done at two bay area tech companies found that about 37% of software engineers rated themselves in the top 5% of skill and quality of work in the company. That’s right, almost one-third of the engineering team thought they were crushing it and were likely confused by why they weren’t getting recognized for it.

These blind spots are partly due to the Peter Principle, which states that people in a hierarchy tend to rise to their “level of incompetence.” The Peter Principle often gets brought up in gossipy discussions about senior leadership, but that misses its most significant implication: most people in a hierarchy are at their “level of incompetence.” This phenomenon is not limited to senior leadership, and it likely also includes you.

This doesn’t mean that you’re a failure and undeserving of the position that you currently hold. It’s usually quite the opposite. You likely had a track record of success which led someone to bet on you and entrust you with even more responsibility. But at some point, your new role required behaviors and competencies that you didn’t have; and even worse, you couldn’t see that you needed them.

I asked Wade to walk us through common challenges faced by engineers and managers at different career milestones.

senior -> staff engineers

Assuming that their technical chops will carry them to the next level: Most engineers arrived at the senior role by solving technical problems of increasing size and complexity. However, larger problems are more likely to span multiple teams or organizations. These projects end up stalling due to a lack of momentum or organizational buy-in. The senior engineer will double down on flexing their technical muscle, oblivious to the fact that interpersonal skills are the hindering factor.

Overly reliant on pattern matching: Another failure mode for senior engineers is not thinking critically enough about the problem. They shortcut to using associate thinking to get to default answers. This type of thinking was enough when they were only expected to contribute to technical conversations, but it’s not sufficient when they are on the hook to get to the best solution.

first-line managers → second-line managers

Not starting from desired outcome: First-line managers are great at building individual connections and growing people. That skill allows them to create a high-performing team with high output that generates value for the company (team → output → value).

However, second-line managers need to flip the direction of that thinking. They should start with what the company needs and work backward towards what outcome the team needs to generate and have that dictate what team or individual changes need to happen (value → output → team).

Struggling: Identifying the gaps that are holding you back

It’s impossible for a person to begin to learn what they think they already know.

- Epictetus

We’ve gone over unconscious incompetence and why it’s so common for people to be oblivious to why they aren’t growing. The next step is to arrive at conscious incompetence, where we still have a lot of gaps in our skillset, but we’re at least aware of what they are.

It’s tempting to skip this step because you feel like you know what you’re not good at. But not all gaps are created equal, and focusing on the wrong ones will see most of your efforts wasted.

Why do we fail to identify the correct gaps? Most of us employ a passive strategy of gap identification. We wait for a failed project or critical feedback to hit us in the face, and then we go: “Aha! This is what I’ll work on!” However, this reactive approach to self-improvement rarely leads to focus on the essential things (just the loudest ones), and its shortcomings become more acute the more senior you are.

I fell into this trap the first time someone gave me their two-week notice. A manager always remembers their first churn, and mine happened during a walking one on one. The notice came with a long list of things that I could have personally done better to retain this individual. I immediately swarmed the problem and spent the new few weeks investing in and successfully improving each person’s relationships and engagement in my team. To my surprise, when my manager found out, he thought I was wasting my time. From his perspective, the team’s engagement had always been excellent; instead, I needed to focus on reducing the regressions going out with every release.

It wasn’t that the team’s engagement wasn’t important (it was); it just wasn’t what was actively holding the team (and me) back. My failure to actively look for gaps caused me to jump onto the first one that presented itself.

How do we identify the gaps that matter?

Before you lock yourself in a cabin in the woods and beautiful-mind all your faults on a wall, here are a few questions that you should consider instead:

What makes you angry, frustrated, nervous or anxious?

The things that make you uncomfortable are often an indication of an area where there’s a lot of friction, outcomes are subpar, or you aren’t confident about your ability to deliver. Following that thread will often lead to a set of gaps in your belief, behaviors, or competencies.

How can you 2x your output in a year?

If you had to double your personal output in a year, what would you do? What behavior or competencies are holding you back from producing more, having more responsibility, and delivering more impact? If you are in a leadership position (management or IC), how can you help the team 2x its output in a year? Are there ways to tighten up existing execution? Or is a significant shift in people, process, or culture necessary.

Who is the best person you know who is amazing at this role?

Is there someone who is absolutely amazing at this role? What are they doing? What makes them great?

Don’t just settle for someone good; instead, find someone who sets the bar! What are the behaviors and competencies that causally make them great? It’s worth emphasizing that what you’re looking for are the causal factors that make them successful and not just any skill they might be good at. An excellent way to find out is often to talk to them about it or find multiple people that are successful at the role and see what they have in common.

It’s tempting to go through this gap analysis alone, after-all, it’s uncomfortable to let others into our shortcomings. However, you can learn a lot about your gaps from an outside perspective; and the best outside perspective on the subject is your current manager.

Involving your manager gives you two benefits:

- Perspective: Their familiarity with your work puts them in a great position to see your blind spots.

- Support: The very act of involving your manager primes them to give you better and more frequent feedback and access to opportunities.

This is one of the many reasons to actively build a strong relationship with your manager, one that is characterized by trust and safety. It makes vulnerable conversations about weaknesses not only possible but welcoming.

Practiced: From zero to hero

Some people get twenty years of experience, while others get one year of experience… twenty times in a row.

-Angela Duckworth

Once you’ve identified the gaps that are holding you back, it’s time to move to conscious competence. This stage is marked by effort but also the reward of seeing the beginnings of success from deliberate practicing of skills.

First 10%: declarative knowledge

The first step of learning anything is to gain a formal understanding of the subject. The good news is that for any subject you’re trying to learn, there’s likely someone who spent years studying it, and most of them have written their thoughts down somewhere. Find these credible sources and consume their books, documentations, and presentations. Reach out to people inside and outside the company. It’s surprising how many times they are willing to chat.

Wade’s litmus test for checking your declarative knowledge is: Can you confidently give a great TEDx talk on the subject.

Many people stop at the first 10%, assuming they’re done (which explains TEDx talks). However, this is equivalent to a fifteen-year-old who just passed their written driving test thinking they’re an expert driver. They might know the theory behind driving but little of the actual practice of it. What they lack is the hands-on experience that leads to true proficiency.

Next 70%: deliberate practice

In her book Grit, Angela Duckworth records an exchange she had with cognitive psychologist Anders Ericsson on why experience doesn’t always lead to excellence. Duckworth shares that she’s been jogging for several hours every week for over a decade.

Duckworth: I’m not a second faster than I ever was. I’ve run for thousands of hours, and it doesn’t look like I’m anywhere close to making the Olympics.

Ericsson: Do you have a specific goal for your training? Do you have a target in terms of the pace you’d like to keep? Or a distance goal?

Duckworth: Um, no. I guess not

Ericsson: I think I understand. You aren’t improving because you’re not doing deliberate practice.

Many of us approach our professional growth like Duckworth approached jogging, focusing on quantity of practice over quality of practice. We carry this from the beginning of our careers where showing up was enough because everything was a stretch goal back then. However, as we progress through our careers, passive learning opportunities diminish, and growth flatlines. In fact, Wade emphasizes that:

The higher you go, the more specific and deliberate learning needs to be.

Even though deliberate practice is the longest step in the entire framework, it’s the least useful to write about. Much of practice is specific to the skillset you are looking to build, and the things that are generally applicable have been written extensively by much more insightful experts than me.

Last 20%: mentorship

By the time Wade joined Twitter, he had been a VP of Eng for 15 years. However, he found that he didn’t know how to influence a large organization. Wade looked around and found a few individuals who were consistently listened to and acted upon. He sat down with them and asked them for advice on how he could improve in this area. Wade took every opportunity to practice influencing and run his talking points or writing through these mentors who helped him hone this skillset.

Finding experts at what you’re trying to learn and having them give you specific and actionable feedback can accelerate and raise the ceiling on your learning.

Should I stay or should I go?

The last thing worth discussing here is the age-old question: Is growth easier if I stay in one company or go to a new one?

Wade’s advice is: be honest with yourself and look in the mirror. Are you looking for someone to fix you? Are you hoping that a reset will magically work?

There are switching costs to go from one company to another. You have to build a new relationship with the manager, learn a new tech stack, etc. Often, these things feel like growth because you’re learning something. But when you zoom out, you’ll often realize that these learnings don’t enable you to get to the next level because they weren’t the gaps that were holding you back. On the other hand, if you know where your gaps are, and neither practice nor feedback is available at your current company, it might be appropriate to go somewhere that excels in those areas.

Mastery: Consciously choose to close the gap!

For everyone of us, there is a gap between who we are and who we want to become. There is a gap between where we are and where we want to be. What helps us close those gaps are the small things that we consistently choose to commit to over and over and over

-Joshua Medcalf

By identifying your gaps and deliberately practicing your competencies, you can finally reach a state of unconscious competency. You’ve practiced the behaviors and competencies for the role to such an extent that they’re now virtually automatic. And as your reward, you’ll gain the time and mental energy to start the cycle all over again.